Optimising Africa’s megacities

Africa News, 20 April 2012, By Kaci Racelma

As African cities implode, leaders on the continent are intensifying efforts to address the challenges of urbanization. A forum bringing together Africa’s housing ministers was recently held in Nairobi, Kenya on 20 March 2012 under the auspices of the African Ministers Conference on Housing and Urban Development (AMCHUD).

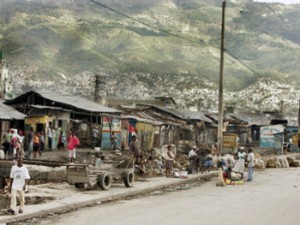

UN Photo

The 4th annual meeting focused on territorial planning and access to basic services for all. It also looked to integrate climate change issues for a smarter more sustainable urban development. In the last 7 years, the conference has allowed members to share ideas and discuss effective strategies in line with the “cities without slums” initiative that was originally adopted in 2005.

For some slum dwellers on the continent, it’s just talk. “I am only interested in being removed from here, to live in a more decent environment,” says Rachid Lashab, who lives in the Essekouila slum in Casablanca. “I am not interested in the many conferences that our leaders attend.”

Crowding and disease

According to estimates by UN-Habitat, 200 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living in slums in 2010, or 61.7 per cent of the region’s urban population, the highest rate in the world. North Africa had another 12 million slum dwellers; that was just 13.3 per cent of its urban residents, the lowest rate in the developing world.

The lack of adequate sanitation, potable water and electricity, in addition to substandard housing and overcrowding, aggravates the spread of diseases and avoidable deaths, according to a recent report of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Slums contribute to low life expectancy. In Mali, for example, more than 80 per cent of the population lacks good housing and average life expectancy is just 51 years, according to the UN Development Programme.

Mali’s situation reflects that of much of sub-Saharan Africa. Fofana Gakou Salamah, Mali’s former minister of housing, land affairs and planning, urged urgent measures from Africa’s housing ministers. “We must take decisive action,” she said. “Otherwise there is the risk of having an urban population [in Mali] of about 6 million souls still living in informal settlements by 2020,” or nearly twice the current number.

Jugurtha Ait El Hadj, an Algeria-based urban planner, believes that African ministers are on the right course. “Such meetings are especially helpful in that they allow exchange of experiences. But these meetings must be accompanied by concrete steps.”

There are many roadblocks to achieving the dream of cities without slums. Algerian Minister for Housing and Urban Development Nouredine Moussa noted that the expansion of cities in Africa limits the ability of national and local governments to provide security and supply basic social services in health, education, water and sanitation.

[click to continue…]