India outlines plans for National Urban Health Mission, The Lancet, Volume 380, Issue 9841, Page 550, 11 August 2012

Soumyadeep Bhaumik

The Indian Government is planning to launch a new urban health-care programme in its latest step towards universal health-care coverage in the country.

In a recent speech at one of India’s premier medical institutes, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh talked publicly about the government’s plans to launch a special programme aimed at improving the health of the urban population. Termed the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM), the initiative will follow on from the flagship National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) launched 7 years ago to improve access to health care in rural parts of India. The Prime Minister also expressed hope that the two programmes together will in the future lead to a unified National Health Mission.

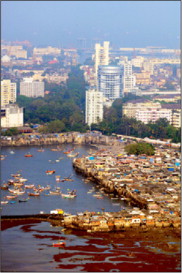

In 2005, the NRHM launched with the aim of improving the then abysmal health-care delivery system across rural India. The NRHM, though marred with issues of poor governance and corruption, has been instrumental in improving several health indicators particularly with respect to maternal and child health. However, unlike the millions who benefited from the rural programme, the urban poor, owing to the absence of any comprehensive health programme, have largely been left to fend for themselves. NUHM is set to cover the country’s seven big metropolitan areas and 772 cities with a population of more than 50 000 people. The government plans to invest more than INR225 billion into the health-care sector via NUHM.

The past decade in India was witness to rapid economic growth. With greater economic opportunities there has been an exponential rise in the urban population, especially in unorganised slums. Harsh Agarwal, previously a consultant with the Planning Commission of India, explained the rationale behind the NUHM to The Lancet: “With the growing urban population, the demand for sanitation, drinking water, electricity, shelter, and health care is set to grow. Since the majority of the migrant population are daily wage workers and marginal labourers, it becomes highly important for the government to provide free access to basic health-care facilities to urban poor. The urban areas have their own challenges and difficulties in meeting the health-care needs different from rural settings thus it is essential to start a separate programme like NUHM, which is designed to cater to the needs of urban poor.”

The urban population makes up about 31% of the population in India. According to estimates, urban centres are growing at the rate of more than 5% yearly. Chandrakant Pandav, professor and head of the Centre for Community Medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, citing the third National Family Health Survey, adds: “Unplanned urbanisation brings forth a whole set of new health problems. [The] urban poor are three times more likely to die before attaining the age of 5 years, 20 times more likely not to have any antenatal care, three times less likely to get primary immunisation, and two and a half to three times more likely to be stunted and wasted than urban richest.”

The NUHM will focus on improving health-care delivery and public health systems. “City-specific planning based on the spatial mapping of the slums and slum-like habitations as well as the existing health facilities; rationalising the available manpower and resources and partnering with private providers and NGOs [non-governmental organisations] for filling gaps; and improving access and quality health services by regular outreach camps and referral services” will all be part of the NUHM, informs Pandav.

The absence of a comprehensive health system has meant that a multitude of agencies now deliver government-aided services. With no coordination, this predicament has only led to confusion and increased inequalities. NUHM hopes to change this situation and is also expected to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure and health inequalities. Pandav explains that, “When the urban poor access private facilities, the significant cost incurred leads to severe debt.”

Agarwal feels that, “The biggest challenge in implementing NUHM would be to ward off the influence of private medical practitioners who would see this scheme as a dent to their private practice.”

Kunal Saha, president, People for Better Treatment, an NGO in India also laments about the loss of public trust in the medical community owing to unregulated private practice and corruption in urban as well as rural areas: “[The] Indian Government must first assure an honest and transparent medical regulatory system for proper control of medical education and practice by doctors/hospitals before embarking on expansive projects with big names if there is any hope to restore public trust and promote a better health-care delivery system.”