Source: SciDev.Net – May 2, 2012

From small-scale hydro-powered electricity in Malaysia to cost-saving solar pumps in Pakistan, communities across the developing world are devising ingenious solutions to improve their livelihoods and promote sustainable development.

They face many hurdles — from fostering collaboration between community members and technical experts, to acquiring funding to take their innovations to market.

But despite the difficulties, grassroots innovation is certainly flourishing.

SciDev.Net spoke to five organisations about their goals, challenges and successes.

Walking the walk

Aziph Mustapha, chief operating officer of the Malaysian Foundation for Innovation (YIM), believes hardship and the need to use locally available resources are the major drivers of novel technology development.

Last year he started a programme called Innovation Walk to seek out knowledge and creativity in Malaysia’s remotest communities.

It involves researchers, government officials and patent experts travelling on foot to visit communities and provide advice on enhancing and commercialising rural innovations, and offering training on related intellectual property issues.

The first walk, in July last year in the state of Melaka, identified 17 promising grassroots innovations, six of which were chosen for commercialisation by Cradle Fund Sdn Bhd, a Malaysian non-profit organisation.

Mustapha gives the example of a villager in Dalat, Sarawak, who used a redundant car engine to design a machine that can separate the husk from rice, speeding up processing for all the families living in his long-house community.

“The entire village has been going to him for the past ten years for this service, which he doesn’t even charge for. He is happy to help the community,” Mustapha explains.

Since the success of the initial walk, Mustapha has organised another 14 similar walks over the past year to remote areas of the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak.

Mustapha says that Innovation Walk aims to unveil innovations that not only benefit local communities, but also help to conserve their natural surroundings and its biodiversity.

To judge from the feedback, the programme is widely appreciated. Hamid Yasmin, a 43-year-old man from Libang Ulu village, says in a comment on the programme’s website that he was surprised to see that government officials and people from YIM had come to his village to look for new technologies.

He says he was delighted when they decided to work on improving his mini-hydro technology, which is already providing electricity for 40 houses. Studies of the design are underway.

The programme continues to face many challenges, Mustapha says, including a lack of understanding among many community leaders on what defines innovation. This is particularly problematic, as these individuals are responsible for highlighting potential innovations from their villages.

“Sometimes they overlook really great innovations, and try to push ‘average’ innovations that may not be so interesting to us,” says Mustapha.

And despite involvement from Cradle Fund Sdn Bhd, there are not enough opportunities to fund interesting innovations.

“Not many funding organisations are interested in providing seed funding for village innovators,” says Mustapha, adding that the innovators identified in each walk often lack the education, experience and track record that funding organisations look for.

But he remains optimistic.

“In my opinion, grassroots innovation is thriving, vibrant and can play a tremendously important role in [turning] Malaysia into a developed nation by 2020,” he says.

“We are out to correct the misconception among some citizens that Malaysians are not an innovative lot. Innovation Walk will prove that Malaysian are, indeed, very innovative.”

Social inclusion

Argentina’s RedTISA (the Argentinean Network of Technologies for Social Inclusion) fosters a very different kind of grassroots innovation. It aims to generate and implement integrative solutions for sustainable development and social inclusion.

RedTISA defines technologies for social inclusion (TSI) as being “oriented towards solving social inequalities and environmental problems”.

“It is not just about the technical aspect of a problem, but also its social component,” says RedTISA executive coordinator Paula Juárez. “Both must be considered equally.”

Inspired by the Network of Social Technology (RTS) in Brazil, RedTISA was set up in June 2011, with a view to fostering relationships between those with relevant technical expertise and communities in need. It is working with around 70 institutions, including government agencies, universities, non-governmental organisations and local cooperatives.

It has also assembled a database of more than 300 case studies of best practice in Argentina, with a focus on food security, health, alternative energy and housing.

Juárez says the team has good evidence to suggest that attempts to solve problems relating to sanitation or sustainable agriculture have relied too heavily on technical solutions and failed to consider the culture, needs and interests of each community.

For example, a native community in Mendoza — the Huarpe — which lacked access to clean water and the energy grid, was given solar water filters.

But technicians installing the devices ignored the Huarpe’s organisational structure. They tried to implement the technology with families one by one. When they knocked on doors to install the filters, they were turned away.

The problem was solved when they involved the local ‘presidents’ and addressed the community as a single entity.

Beyond this, Juárez explains, effective problem solving means more than providing the necessary technology, but also organising a support network within a community, to solve any issues that arise after the technicians leave.

The only way technologies will be accepted into local communities, Juárez says, is if the community participates in the entire process, from choosing the most appropriate innovation to training people to harness it.

She gives the example of Villa Paranacito, a small flood-prone community in the Argentinean province of Entre Ríos. A local research centre used local natural resources such as poplar wood to rebuild houses destroyed through flooding. The entire community was involved in the rebuilding work from design to construction, and also learned how to treat the wood to prevent pest attacks.

RedTISA is now overseeing a programme of study focusing on TSI at the Federal University of Latin American Integration (UNILA) in nearby Brazil. This three-month course started in March 2012, and RedTISA is already receiving requests to replicate it at other universities.

Juárez says this will help students recognize the need for new thinking about development processes, and to understand that working with workers in self-managed companies and cooperatives is economically viable and sustainable.

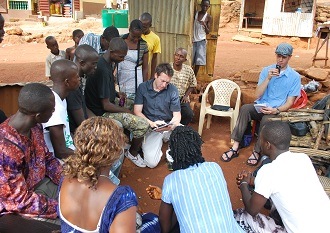

Working together

Working together is the ethos of Baanhn Beli in Pakistan, which means “a friend forever” in the Sindhi, Seraiki and Punjabi languages.

It was established in 1985 by Javaid Jabbar, who has previously served as Pakistan’s minister of science and technology, and of information. He had visited Tharparkar — the most marginalised district in Pakistan’s Sindh province — and been struck by the lack of food, water, basic sanitation and healthcare for its one-million-plus inhabitants.

Since its inception, Baanhn Beli has implemented development programmes in agriculture and water resources, livestock management, female education and healthcare, female empowerment and microcredit that aim to meet the specific needs of local communities.

Its primary focus is on introducing appropriate, well-established technologies to the area, but it also facilitates the development of local innovations.

Baanhn Beli works largely in Tharparkar, where local communities rely heavily on non-governmental organisations for development support.

As well as running development programmes, Baanhn Beli encourages direct participation by locals in all activities, and fosters cooperation between locals and a range of other stakeholders including rural-based volunteers, local government bodies and others.

“We want to work on capacity building with the Thari people so that they can solve their problems on their own,” says Mohammad Khan Marri, president of the organisation. “All we do is show them how.”

One of the project’s biggest successes has been developing dams to help conserve precious water resources. Tharparkar District is outside the River Indus basin, and locals frequently experience drought, as they rely mainly on rain and groundwater for water supplies.

In 1994 — with help from the local community — Marri started building micro dams in the Karoonjhar hills in Nagarparkar, one of Tharparkar more remote areas. That year, heavy rainfall provided a reservoir for the people.

The work also raised the groundwater table, refilling an empty well. Locals called the micro dam “Maya”, which means “great wealth”. The water supported cultivation and livestock, as well as human water supplies.

“I was simply overjoyed to see the villagers and their animals drinking water from the dam. That was the happiest moment of my life,” says Marri.

So far, Baanhn Beli has constructed 12 dams, mainly in Nagarparkar, that collectively irrigate 2,500 acres of agricultural land, compared to the 50 acres that were irrigated before the dams were built. Some 35,000 people also rely on the dams for personal water supplies.

The organisation has also equipped farms with solar pumps, which are significantly cheaper than diesel versions. Ten pumps have been installed so far, enabling the farmers who use them to triple their income.

Arab talent platform

In Egypt, a lone organisation is hoping to take grassroots innovations to the next level — commercialisation.

In 2005, just 0.5 per cent of the 25,000 patents held in Egypt’s patent office had been commercialised. This inspired Atef Mazhar to set up the first Arab non-governmental organisation dedicated to supporting, implementing and marketing grassroots innovations.

Mawhopon — which means “talented” in Arabic — was established in 2006 by Mazhar and a group of interested individuals, including academics and journalists. It is an internet platform through which Arab innovators can showcase ideas and products and attract potential investors.

By 2009, the initiative had compiled a database of 2,000 innovations, and had also received the 2009 Salem Al-Ali Al-Sabah Informatics Award for best Arab development website.

“Grassroots innovation is one of the main challenges for development, and in our region, grassroots innovators have [particular] difficulty in finding anyone to support them,” Mazhar says.

He says that in the Arab region, there is a distinct shortage of specialist organisations devoted to helping innovators take ideas through to market. The best most innovators can do is to obtain a patent — then they are on their own. Historically, the only way to attract investors to support an invention has been to produce a prototype, which is expensive.

“We had to help innovators who held patents to produce a marketable prototype of their innovations and conduct feasibility studies. But before we could raise the funds to do this (through targeting international organisations interested in supporting innovation), Mawhopon needed to be legally approved by the government,” Mazhar says.

“The Arab spring had a large influence not only on the political situation in Egypt, but also on the very complicated procedures involved in setting up a non-governmental organisation,” explained Mazhar, adding that Mawhopon was legally launched at the end of 2011 — meaning that it can now fundraise on a large scale.

While awaiting formal approval, the organisation decided to help individual innovators build prototypes of their invention and get them tested by a committee of volunteer scientists, and involved them with events where they could showcase their work.

One of Mawhopon’s success stories is that of Yosri Ali Madkour, an Egyptian engineer, who invented a wave-powered desalination unit, which he has patented with the Egyptian Patent Office. The idea involves a vapour compression apparatus that is contained within a floating unit. The internal wave motion generates pressure that drives evaporation and condensation of fresh water.

Madkour wrote about the invention on Mawhopon’s website in early 2010 and several interested investors offered to help him build a prototype.

“Finding appropriate funds to [develop] a prototype is a key obstacle that faces inventors in our region,” said Madkour. “Mawhopon has helped me to overcome this.”

Since its legal approval, Mawhopon has gone from strength to strength. In February this year, it entered a partnership with the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology (ASRT), the government body responsible for funding research in Egypt, to form a scientific committee to study grassroots innovations and approve them so that they can taken to market more quickly. It will also help link innovators with investors.

“The two first ideas we delivered to the ASRT committee were a probe to locate landmines, and a green unit that harnesses solar power to desalinate water cheaply,” says Mazhar. “We are expecting the results soon”.