Mobile phones call out for fresh water | Source: BBC Future | Nov 5, 2012

An innovative system being tested across Kenya allows people to access drinking water at the touch of a button.

Spencer Ochieng is in the business of connecting remote villages in Kenya with water. But to do so he relies on an unusual tool. When most people dig down to check the water table below, Ochieng digs into his right pocket.

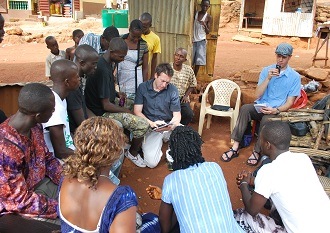

“The first thing we check for is availability of a strong mobile phone signal,” says Ochieng, general manager of Grundfos Lifelink, an organization that uses technology to provide safe drinking water to communities throughout the developing world.

Water dial The Lifelink system mixes mobile technology with a solar-powered pump to provide freshwater to paying customers throughout Kenya. (Copyright: Jonathan Kalan)

Currently, there are nearly 1 billion people around the world with no access to clean water, and 13 million in Kenya alone with no access to a so-called “improved water system” – NGO-speak for anything that improves on collecting dirty water from rivers, lakes or ponds.

The Lifelink project was set up to tackle this problem using a solar-powered pump and a pay-per-use water tap, designed specifically for Kenya’s mobile-centered society.

The setup is relatively simple. Protected water is drawn from sources up to 250m underground by solar powered pumps. This is then held in an elevated storage tank, which is used to supply a tap in a secure, concrete kiosk. To access water, customers must first load money into their M-Pesa account — the ubiquitous mobile money payment and transfer service in Kenya used by more than 70% of the adult population. Then, through a simple text message, customers top-up the balance of their personal pre-paid Lifelink fob key. Once at the tap, customers simply wave their key at a sensor; money is debited from their account, and out flows 20 litres of pure drinking water.

“There’s a real need to provide drinking water to communities in a sustainable way,” Ochieng says. Every year thousands of deep wells, pumps, and boreholes are installed across the African continent by development organizations. Unfortunately, when funding dries up, so too does the water source. Studies have shown that as many as half of these projects are no longer working after two years. Pumps break. People stop paying. Wiring erodes. Parts vanish.