Several years ago, USAID Chief Innovation Officer Maura O’Neill and Harvard economist Michael Kremer came up with an idea of a new model to help find bold development solutions. Building on their respective expertise in venture capital and economics, they wanted to find a way to harness the power of innovation, and ground it in rigorous testing to create a system with the potential to scale proven solutions to millions around the world. In late 2010, USAID’s Development Innovation Ventures (DIV)—USAID’s investment platform that finds, tests and scales new solutions to development challenges around the world—was born.

Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) is USAID’s venture fund for finding and testing new solutions to challenges in the developing world. DIV’s goal is to find, test and scale ideas, in any sector and country, that will sustainably and cost-effectively improve the lives of millions around the world.

Stage 1 – Proof of Concept: Projects establish proof that their approach works, and show the potential to sustainably and cost-effectively reach millions.

Stage 2 – Testing at Scale: Investments test promising ideas at scale to gather more evidence of their impacts and costs.

Stage 3 – Widespread Implementation: Grantees transition proven solutions to wider scale across multiple countries.

“What we are trying to do is be a global one-stop shop for a good idea,” says Jeff Brown, director of the DIV program. “We are open in any country, any sector, and to anybody who has an idea that they can solve a development challenge in a more cost-effective and evidence-based way.”

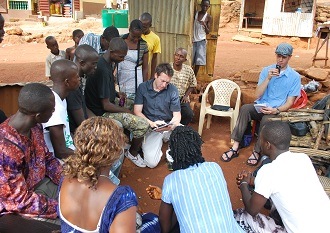

To find the best ideas, the program holds a year-round competition that opens the door of USAID to both traditional and nontraditional partners anywhere in the world, whether a young entrepreneur in Uganda creating green fuel alternatives, a student at MIT building a new business model for sanitation in urban slums, or a coalition of partners testing behavior change interventions in traffic safety. In fact, 70 percent of applicants to DIV’s competition are new to USAID.

“It’s complete open innovation,” says Brown. “If you have an idea, pitch it to us in a five-page business plan and we will vet it.”

As in the venture capital world, there is a realization that not all ideas that win USAID support will move mountains. While some will scale, some will need to be modified or abandoned. To manage this risk, DIV invests in ideas in three stages.

“We go in relatively cheaply at the beginning, and if there is more evidence and things continue to prove out, we will put in a little more, and potentially even a little more,” says Brown.

At each stage, DIV selects proposals that best demonstrate their plan to gather evidence of impacts, their potential to be more cost-effective than other approaches, and their pathway to scale to millions without long-term DIV support if proven effective.

To monitor the success of the projects, DIV selects ideas that rigorously test their social impacts.

“Built into each project is an evaluation component,” says Wes Day of the DIV team, who manages many of the program’s grants. This way, USAID can ensure, for example, that increases in farmers’ crop yields are the result of improved fertilizer use, rather than increases in rain that year. Projects can gather evidence using a range of tools. Fifty-four percent of grantees use randomized control trials, a testing method borrowed from pharmaceuticals to compare groups that receive the intervention with groups that don’t. Others use more market-based tests to build a case for the sustainability of commercial products.

All grantees also test the cost-effectiveness of their project relative to alternatives. By finding more cost-effective ways to solve development problems, the DIV program seeks investments that can achieve more impacts per dollar, and achieve greater good, at greater scale, for less. In one example, a DIV grantee in India is implementing a mobile health tool to rural health workers that allows them to provide better treatment to patients for $86 per year per worker, relative to the thousands of dollars spent by the Indian government to train the workers with the same skills.

While some ideas in the DIV pipeline start small, the ultimate goal of the program is to nurture those ideas that can have transformational scale and sustain themselves without USAID funding, says Kristen Gendron, another member of the DIV team. “We look for ideas that, once proven, will scale to millions through either the public sector or the private sector,” she says.

For example, a DIV grantee can use its USAID funding to demonstrate the profitability of its solar panel business model in order to incentivize investments from the private sector. Or the grantee can gather evidence that its approach to providing safe drinking water is a better way of spending public dollars so host governments invest in bringing it to wider scale.

Over the past two and a half years, the DIV model of open-source innovation, rigorous evidence-gathering, and staged-financing has resulted in over 70 investments totaling roughly $30 million in funding from DIV and its partners in 24 countries and counting.

http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/frontlines/open-development-development-defense/ventures-innovation

Reaching rural areas in Kenya, Uganda and beyondJonathan Kalan

Reaching rural areas in Kenya, Uganda and beyondJonathan Kalan